Finding a balance between access to info and privacy

Disclaimer: Until September 2017 I was a Technologist at (CNIL) the French DPA working on the technical aspects of issues like the right to be forgotten.

On June 28, a decision of European Court of Human Rights reanimated the debate about the Right To Be Forgotten. The court rejected the request to delete some content on a website, considering that the right to access to information prevailed. The court made an interesting distinction with the Right To Be Forgotten applied to search engines. Search engines and publishers have different purpose so the ECtHR refers to ECJ decision for the search engines.

Because the decision on the Right To Be Forgotten is sometimes misunderstood, I try to explain why, in my opinion, the Right to be forgotten as proposed by ECJ should not interfere with access to information.

The right to be forgotten and public’s right to access lawful information

In its decision about the right to be forgotten, the ECJ anticipated the risk that this right could limit access to information and asked for a balance between the personal right to privacy and the public right to access information. In ECJ words, right to be forgotten should not apply “if it appeared, for particular reasons, such as the role played by the data subject in public life, that the interference with his fundamental rights is justified by the preponderant interest of the general public in having, on account of its inclusion in the list of results, access to the information in question.”

Sure, finding the balance is not always easy, but CNIL and Google tend to agree on cases where the right to be forgotten should not apply. As a matter of fact, in the first case that Google mentions in its post, Google is not the defendant: CNIL is. Indeed, the case were rejected by Google and the concerned persons sent a complaint to CNIL, but CNIL agreed with Google that this was going against interest of the general public in having access to information.

So while many fear that an extended right to be delisted will impede on access to information, this fear is not founded. The ECJ decision clearly strikes a balance between the right to be delisted and the right to access information. The objective of the decision is not to force information to be deleted, it is to prevent unwanted – and often out of context – search results from popping up when you Google someone. The results are still available on Google and will appear as usual if you search anything but the name for which the results have been delisted. As a matter of fact, the information is not censored, it remains available on the website publishing it but it won’t appear out of the blue when you’re just googling someone’s name. This is somehow coherent with ECtHR decision: publishers are fully covered by freedom of expression but search engines main goal is not to publish information but to compile information about someone (paraphrasing p.97 of ECtHR decision).

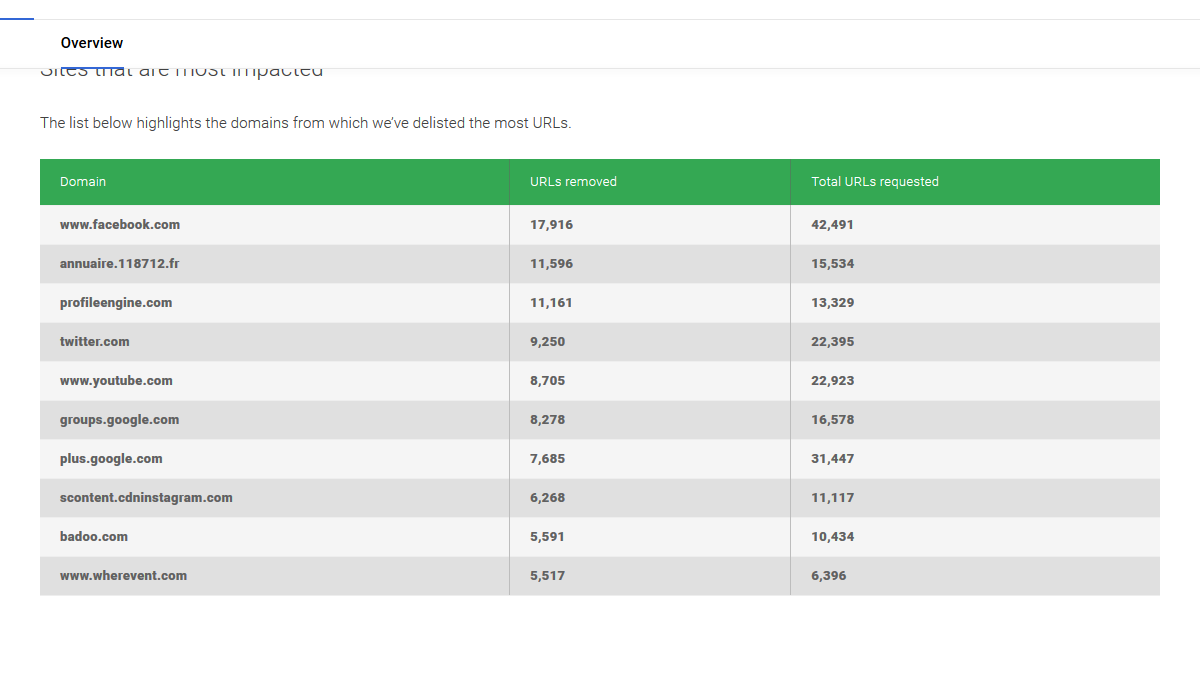

The case ECtHR had to judge is an edge case and it seems that when it comes to RTBF applied to search engines, most cases are way more simple. If you want to understand the reality of what is at stake here, have a look at data provided by Google: the top 10 websites for which Google delisted results are social networks. Most of the complaints concern people asking to have comments, pictures and posts removed from social networks. In some cases the content is hosted by Google itself (e.g. Google Plus, YouTube) so individuals have no other remedy than asking Google to delist its own content when it’s inappropriate. Would platforms prefer to directly suppress such content?

Google shall no longer be the only place where we look for information

Google no longer oppose the Right to Privacy to Freedom of speech (as it used to) but to the public right to access information. Despite the goal of Google to “organize the world information”, Google shall no longer be the only place where you look for information. Search engines algorithms are not meant to find true information, but to find information provided by authoritative sources. That’s why algorithm ranking failures have been observed repeatedly over a year.

Wall Street Journal’s Jack Nicas listed some failures of the featured snippets which are supposed to be the most trusted results provided by Google. Just a year ago, Google was displeased by top results provided by its algorithm and had to deploy patches hastly . While the company should be lauded for its reactivity, it should be noted that this reaction has been triggered by journalists discussing highly visible problems. Obviously, some reaction had to be triggered, but addressing only the cases reported by the press leaves the main problem pending. In fact, Google picks and chooses the search results that it believes are wrong and thus Google no longer consider the page authority to decide what are the most relevant results, it relies on media attention. It’s not the first time that Google had to update its algorithm hastily. In 2013, reporters highlighted that mughshot websites were highly ranked by Google and were doing some extorting ex-convicted: individuals had to pay for their records not to appear on top of Google search results. A right to be delisted would clearly have had an interest there, but Google shortcut the regulators and updated its algorithm to « fix » the problem shortly after the NYT reported the matter. Last November, Eric Schmidt declared that Google will “derank” Sputnik and Russia today (two Russian websites). Another patch developed promptly to postpone problem and hide it in the “next” result pages. Individually, these decisions seem laudable. However the big picture shows Google judging what is right and what is wrong and hide the « wrong » results by ranking them in such a way that it cannot be discovered without clicking next a couple of additional times.

Google is not the Internet (and it’s not the Web either)

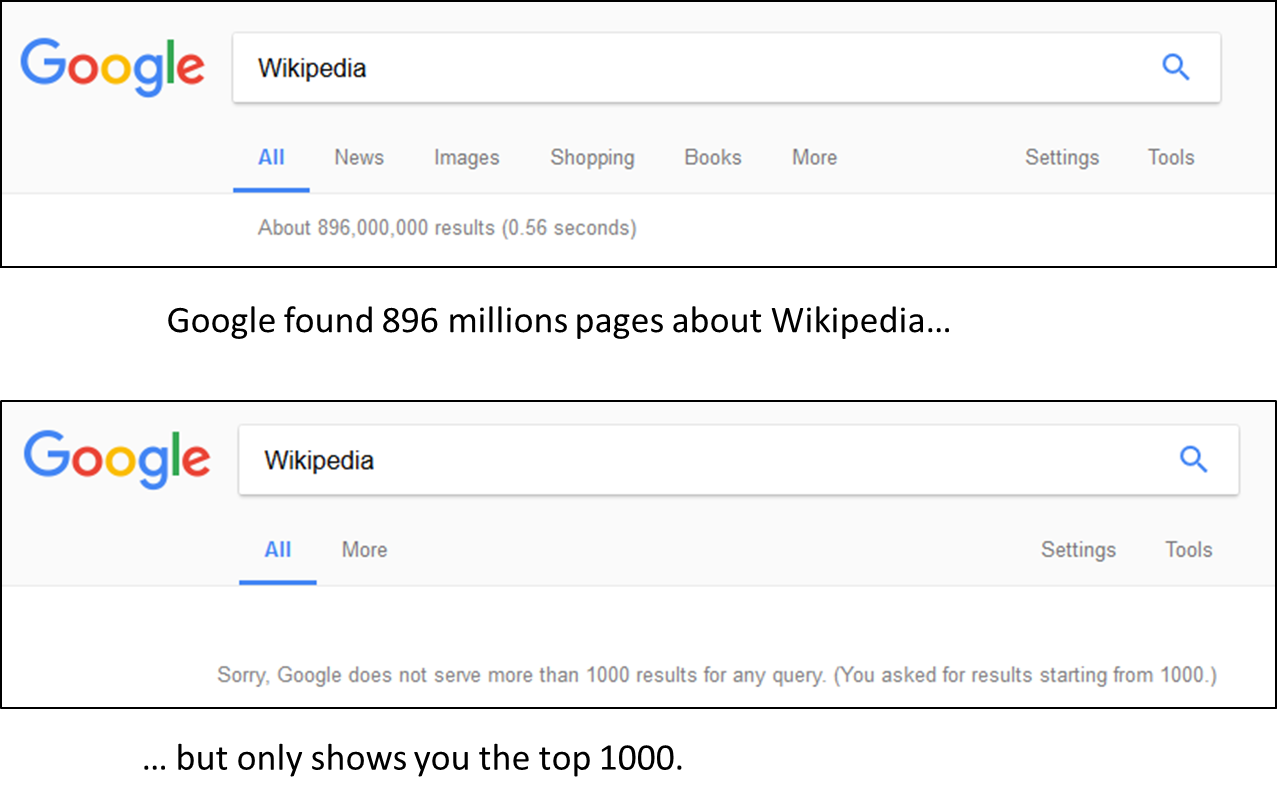

If you worried that article with very low ranks will not be seen you’re right, Google never returns more than 1000 search results per query. Practically, if people rarely see the 11th result they never see the 1001th: results following the 1000 results are as good as delisted. So among the millions of results that Google found (and you can see the exact number just below the search bar), Google will only show you 1000. Therefore it’s not because information is not available on Google that you should not keep searching for it.

Google is not the internet. The vast majority of internet websites are hosted by and operated through service providers other than Google. The entities with the technical ability to remove websites or content from the internet altogether are the websites’ owners, operators, registrars, and hosts—not Google. Removing a website link from the Google search index neither prevents public access to the website, nor removes the website from the internet at large. Even if a website link does not show up in Google’s search results, anyone can still access a live website via other means, including by entering the website’s address in a web browser, finding the website through other search engines (such as Bing or Yahoo), or clicking on a link contained on a website (e.g., CNN.com), or in an email, social media post, or electronic advertisement. <- These are not my words, they are the words of Google’s lawyer in the Equustek case (see https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/3900043/Google-v-Equustek-Complaint.pdf 15 & 16).

The point is that there are other sources of information: other search engines either concurrent or just integrated on news website. If you’re really looking for public information about someone, you should search his name on a newspaper website or on Wikipedia. A Google search may not return the information you’re looking for and is likely to return out of context information.

Wanted: A right to be forgotten

By merely patching PageRank issues, Google postponed the big debate that the ECJ is now forcing it to have. Many individuals have problems with search results about them appearing on Google but cannot expect a miraculous algorithm update to solve it. These people have to rely on the « right to be delisted» to remove offensive, defamatory our outdated and often untrue search results. The right to be delisted decision highlights the need for a balance between right to simply discover information and privacy, while not questioning the access to information on the web. Beyond the big cases reported by journalist and civic society, many individuals have more private problems with defamatory search result page, revenge porn, old comment that they wrote, pictures they should not have shared. There are not enough journalist and civic society associations to cover all these cases and most of them are not willing to have their complaints exposed by journalists.

@vtoubiana

Credits: Featured Image is “Outside the European Court of Justice” by katarina_dzurekova (Creative Commons)